Meaning, Not Marketing: NZ Agriculture & The Experience Economy

“Farmers appear to be strengthening their balance sheets and de-intensifying their farming systems in advance of ‘something’… they’re just not clear what that something is.”

KPMG, 2018 Agri-Business Agenda

There is a sense of impending transformation ahead for agriculture in New Zealand. For some, it feels like change by necessity in the face of environmental limits, shifting consumer tastes, a redefined social license and the threat of alternative proteins. For others, it’s an opportunity to re-imagine our role as food producers and our impact on the world.

Part one of this series - The Vegans are Coming - argued the case for change by necessity. This post articulates how we might apply a value-add strategy in response. It covers how experience economy thinking, customer-centric value, understanding the value proposition of alternative proteins and identifying our pillars of global leadership could enable a more complete brand story and a truly competitive edge.

This post is about understanding our potential in this new world of food.

Value in the experience economy

Pine & Gilmore tell us that value changes over time. For most of history, value was measured in the amount of rice, iron or other commodity on offer. In the manufacturing age, we added convenience to commodities in the form of goods, before services became even more valuable in the services era. Today, we find ourselves on the cusp on the experience economy, where increasingly affluent and discerning societies see value less in ‘stuff’ or services, and more in intangibles like identity, uniqueness and memorability. Pine & Gilmore use a simple analogy to explain the experience economy - the birthday cake.

First baked with commodity ingredients for mere cents in the agrarian economy, then made from a convenient pre-mix and eventually ordered direct from a patisserie, today’s parent outsources the whole birthday to Chipmunks - complete with ball-pits and party games. They throw in the cake for free.

In this analogy, the discerning parent no longer sees value in the easy-to-come-by cake, but rather in their child’s joy and the memory of the experience - all intangibles, hard to measure but undoubtedly valuable.

Contemporary value is wrapped up in authenticity, status and personalisation. It’s likened to the ‘warm glow’ you experience when giving to charity or a symbolic statement that reinforces personal identity and communicates beliefs.

Visualizing the experience economy

We are hurtling towards the experience economy at pace. Affluent consumers are spending more on unique experiences and less on tangible goods and services. Millennials in particular are driving the experience revolution – 50% value experiences over things and 60% prefer products that speak to their identity. In turn, brands are increasingly reshaping their value proposition to inspire deeper connections with customers. Recent examples include Nike’s controversial endorsement of NFL star and civil rights icon Colin Kaepernick, Patagonia’s endorsement of two conservation-focused US senators and IKEA’s acknowledgment of ‘peak stuff’. The long-term success of these branding exercises rests on the ability to ‘render authenticity’ – to look genuine in the eyes of customers.

It helps to picture value in the experience economy across six overlapping pillars:

Adventures - tourism, Air BnB experiences or even a heavy metal cruise.

Togetherness & Friendship - farmers markets, restaurants or online communities.

Caring – the ‘warm glow’ of charity, volunteering or fair-trade certifications.

Self-definition – your favourite sports team jersey, frequenting a vegan restaurant or being the first to have the latest iPhone.

Peace of Mind & Tradition – terroir in wine-making, community agriculture or grass-fed beef.

Convictions – animal welfare, organic or environmental standards.

Value in the experience economy is a high risk, high reward arrangement. High risk in that it is deeply subjective and requires a commitment to authenticity and quality by producers. High reward in that it creates a relationship between customer and producer that goes far beyond a simple transaction.

Customers come first

Understanding value starts with understanding our customers. They set the rules. Despite a continued rise in global meat consumption (driven largely by higher living standards in developing economies), the value that the world’s richest eaters attach to animal agriculture is undoubtedly changing.

Let’s talk about our target market - the 40 million of the world’s richest eaters. They live in countries where zero or reduced meat diets are experiencing exponential growth. In the US, vegan food as a category grew 20% year to June 2018, more than doubling its growth rate on the previous year. In the UK, up-market supermarket chain Waitrose saw a 70% growth in plant-based food sales. Regulators are also shaping eating habits - China plans to cut meat consumption by 50%, the UK is considering increasing taxes on meat and the UN is calling for other countries to follow.

Wealthy consumers have the luxury of choice and are more likely to take increased satisfaction in purchasing experiences. They can afford to be discerning, not just on quality, but on the meaning they attach to a product. For some, turning away from meat and milk will be their stand against the environmental degradation caused by industrial farming. Others will choose a plant-based diet to achieve their health & wellness goals. Some will choose plant-based foods to fight back at the institutionalised animal cruelty of the modern food system. Given the social currency veganism generates across social media, celebrity endorsement and mass media, many will turn away from meat & milk simply because it’s cool.

This is the experience economy in action, where value shifts from personal satisfaction to participation. For many discerning eaters, value increasingly lies in the intangibles of an animal-product free diet - identity, status, ethics and social currency. Looking more broadly, our customers don’t buy champagne because it tastes better than Methode Traditionalle, but because it’s the pinnacle of heritage, tradition and refinement. They don’t drive a Tesla just because it’s the best on the market, but to play their part in the EV revolution.

Alternative proteins: meaning or marketing?

“We plan to do to animal agriculture what the car did to the horse and buggy. Cultured meat will completely replace the status quo and make raising animals to eat them simply unthinkable.”

Memphis Meats CEO Uma Valeti

In 2021 Memphis Meats plans to commercially launch cultured chicken and duck. Competitors Mosa Meats will launch cultured hamburger meat in the same year and steak is next on the menu.

Looking at the language alternative protein founders and advocates use, we start to understand where they see the real value of their business model. Their pitch transcends taste, place or people. They are asking their customers to join them on a journey to revolutionise an industrial food system buckling under its own weight.

You don’t ‘sign-up’ for Memphis Meat’s newsletter, you ‘join the movement’. Alternative protein marketing can be deliberately confrontational - right down to the names, ‘clean’ or even ‘slaughter-free’ meat. Theirs is a rallying cry to the animal lover, conservationist and economist in us all. Joining the clean meat movement means taking a stand against everything that industrial farming represents, and basking in all the ‘warm glow’, identity signalling and social currency that comes with it.

This campaign for Oatly (a milk-like product created from oats) was banned in Sweden after pressure from industry groups.

Where we are marketing our product’s attributes and starting to tell the Kiwi-terroir story, clean meat is building meaning. When the challengers overcome their scalability and quality barriers, will our grass-fed, marginal emissions, ‘animal-friendly’, Kiwi-story value proposition be equally appealing? Or do we need a movement of our own?

Finding our place in the experience economy

For the most part, value in animal agriculture in NZ is still a case of ‘more-is-more’ - a production focussed model where the customer-producer relationship ends at the farm gate. Recent customer and public scrutiny has questioned several features of the model that impact our clean, green value proposition - our reliance on questionably sourced, synthetic fertilisers, the use of imported supplementary feed, dairy conversions in sensitive ecosystems and water quality to name a few.

But the production first model is giving way. We are starting to play in the intangible value space, experimenting with terroir storytelling in particular to make our products feel uniquely Kiwi. Examples include Beef + Lamb’s Taste Pure New Zealand campaign and consumer orientated brands like Atkins Ranch or Green Meadows Beef.

The ‘national-terroir’ concept worked well for the NZ wine industry in the boom years of the 90’s and 2000’s. Makers built a collective reputation based on terroir qualities like landscape, novel practices and the skill of the growers. As society evolved from the homogenised materialism of the 80’s, the Kiwi-terroir story successfully differentiated our wine and made it special.

But we don’t live in that world anymore.

Terroir storytelling will be a critical part of our value story, but the marketing must front for a deeper meaning to compete in a more challenging market. We are more discerning consumers today, bombarded by storytelling marketing and connected to the ethical, social and environmental consequences of our buying decisions. Where NZ wine was competing in a global market ready to fall in love with wine and New Zealand’s clean, green upstart image, contemporary animal agriculture finds itself as the established player facing shifting consumer trends and a new generation of ‘value-added’ competitors in the form of alternative proteins.

Yes, we farm better than the rest of the world – on-grass, with lower emissions and better animal welfare standards - but unless we build a meaningful value proposition around these features, we risk being dragged down by more industrial producers.

Marketing campaigns about green hills, shining streams and Kiwi farmers have a role to play, but we need to give our customers something deeper in believe in.

The volume to value movement

Already, there are exceptional farmers, organisations and professionals striving to build value into our model. NZ story are building Brand NZ – articulating our core values and furnishing businesses with the tools, research and support to tell a Kiwi story. Te Hono is a business led forum working to make the NZ primary industry a world leader – economically, environmentally and socially. Their ‘Project Leapfrog’ strategic overview covers the pillars of a volume to value shift.

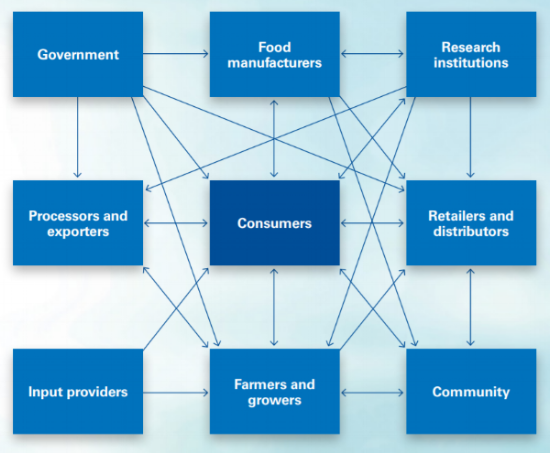

Pāmu (formerly Landcorp) are interpreting Kaitiakitanga (guardianship) in primary production and developing boutique nutrition like sheep and deer milk. The KPMG agri-business team are re-imagining the value chain as a ‘value web’ centered on customers. Pioneering farmers like the Hart family on Mangarara Station are proving that regenerative farming, community engagement and land stewardship offer alternatives to the production first model. On farm environment management support from the likes of Beef+Lamb, AgResearch and others is the groundwork for greener farming and Steve Maharey is articulating how an NZ Food story is a pathway to a higher value economy. There are countless others adding value in their own way.

KPMG’s value web

Pillars of our value story

I’m interested in how our actions on the global stage add intangible value to the food we grow. I see three pillars where our strengths and consumer trends intersect - working towards a net positive footprint, championing animal welfare and prioritising our heritage. These pillars represent opportunities to create a positive feedback loop, where our courage to do the right thing establishes a valuable global brand and incentivises more sustainable farming practices.

1. A net positive footprint

Environmental degradation is the defining issue of our time. We have to acknowledge the fragility of the ‘more-is-more’ production model in our changing world. On farm, we’ll face challenges like prolonged drought, increased flooding and biosecurity breaches. Off farm, we’ll face regulations and a tightening social license to operate. On-shelf, competitors will challenge us with innovative products that offer solutions to the environmental degradation industrial farming helped cause.

To be blunt - either we get our stock numbers down or the market or nature will do it for us.

I recognise the difficulty in that statement. Farmers can’t just cut production and commit to net-positive practices – a 10% stock drawdown would put many out of business. Most are already doing their best to limit environmental degradation within the constraints of the productivist model. The solution lies in redesigning our model so that farmers profit when practicing environmentalism.

Alternative proteins derive intangible value by promising to help the environment – and so should we. We already know that smart land management sequesters carbon and that Kiwi farmers are capable of slashing their emissions, improving water quality and protect more than ¼ of our native forests. We are building a green value proposition by stealth, instead of placing it front and centre of our transition from volume to value. To start, we should seriously consider a national environmental framework like Ireland’s Origin Green to ensure we measure our gains and Fonterra should reward their best farmers and stop mixing their most sustainably produced milk with the least.

The world knows us for being clean & green, so how far could we pull that intangible value lever? What kind of premium could we earn if all NZ meat and milk was certified carbon neutral? What if every NZ lamb chop, piece of cheese or steak was sold with a commitment to increase native biodiversity through reforesting marginal land? How do we get more tourists on-farm to generate value from environmental investments? Could we become the first country to mainstream regenerative farming principles? What if every NZ product was sold in biodegradable packaging like Bostock chicken?

In the same way that alternative proteins derive value from purpose, we can earn our intangible value premium by offering customers real meat & milk that’s not just ‘the least bad’, but a net positive for the environment.

2. Zero cruelty farming

The story of Happy Cow Milk demonstrates the value of a commitment to compassionate farming. Convinced that we can do better than the institutionalised cruelty of modern dairy, Glen Herud set-up a new model that allows for a more natural mother-calf relationship. While the venture has struggled, loyal customers, media exposure, new commercial interest and a clear mission, grounded in empathy, is keeping Glen in business.

New Zealand should be the Happy Cow Milk model for the world - deriving intangible value from a fierce rejection of the status quo and a commitment to our animals.

New Zealand already has some of the highest standards of animal welfare in the world – but the arrival of cruelty-free alternatives will shift the goalposts on the definition of compassionate treatment. Mother-calf separation at birth, the annual slaughter of 1.7 million bobby calves, the 2-7km daily round trip to the milking shed all represent the kinds of institutionalised cruelty that the production first model requires. Instead, we should be focusing on leading the world, unequivocally, in animal welfare and positioning our products to earn a premium from that leadership. New Zealand should be clean, green and kind.

3. Prioritising Heritage

An American style cattle feedlot operating near Ashburton sits squarely at odds with our emerging value proposition and reputation. It’s continued existence is a mistake.

The episode highlights the intangible value between the ‘right’ way to farm, and the ‘wrong’ way. Protecting the dignity of our people, animals and place, or not.

A commitment to our heritage is a value proposition, as demonstrated by the evolution of animal agriculture on Banks Peninsula. A collective commitment to artisanal quality among its farmers, investment in land regeneration and opportunities for visitors to engage with the landscape and history via walks and experiences are building profitability and resiliency into the region.

When we terraform the Mackenzie country into dairy farms, import feed or degrade local waterways, we chip away at the NZ heritage story and jeopardise our ability to render authenticity with our customers.

We can see the value of our heritage proposition through the lens of food safety. We’re number one for food safety because our customers believe that we farm the ‘right’ way. They see first-hand the results of production first farming in their own countries and see in us something better. Our reputation for food safety doesn’t come from following the production first model, but by standing apart from it.

Building the heritage value proposition starts with prioritising our land, history, animals and people and looks like terroir storytelling, agri-tourism and radical transparency. To take the heritage proposition a step further, imagine if Kiwi farmers led a global campaign against feedlot farming – differentiating our product, championing the ‘right’ way to farm and making meat special again, the way our grandparents enjoyed it.

Ultimately, leveraging heritage is about looking back, past productivism, and celebrating a time when we were a part of the landscape, instead of dominating it.

Building a brand - headline by headline

The clock is ticking

By 2021 and the very near future beyond, we’ll see products on shelf that undercut ours by price and outperform us on critical intangibles – social currency, environmental credibility and ethics. We have an uncertain future as food producers in that world unless we acknowledge the limits of productivism and commit to truly farming the ‘right’ way.

But I get it – all of this is far easier said than done. Generations of farmers and processors have poured billions into the infrastructure and knowledge that underpin our current model. And while farmers are an inherently optimistic, entrepreneurial bunch, they can’t do it alone. We need a national transition framework that focusses on building the relationships, know-how, oversight and marketing capabilities that will enable a low production, high value model.

Our challenge now is to remake our animal agriculture system into one that heals the environment, champions animal welfare and celebrates the best parts of our heritage.

We’re Kiwis – if anyone can do it, we can.